John Beckett reviews Nottingham in the Great War by Carol Lovejoy Edwards

One of the more heartening aspects of the First World War commemorations is that they have not concentrated purely and simply on the Western Front. There are, without any doubt, plenty of reasons for remembering the great slaughter which took place in Belgium and France, particularly during the ‘trench’ period of the conflict, quite apart from the linked conflicts elsewhere in Europe and further afield . But there are also many reasons for remembering the home front, not least the fact that so many families lost members in the conflict and were often left simply to get on with life. Bodies were not repatriated, so the best they could hope for was a name on a war memorial, and perhaps a few personal possessions which might reach them many months after their relative died.

One of the more heartening aspects of the First World War commemorations is that they have not concentrated purely and simply on the Western Front. There are, without any doubt, plenty of reasons for remembering the great slaughter which took place in Belgium and France, particularly during the ‘trench’ period of the conflict, quite apart from the linked conflicts elsewhere in Europe and further afield . But there are also many reasons for remembering the home front, not least the fact that so many families lost members in the conflict and were often left simply to get on with life. Bodies were not repatriated, so the best they could hope for was a name on a war memorial, and perhaps a few personal possessions which might reach them many months after their relative died.

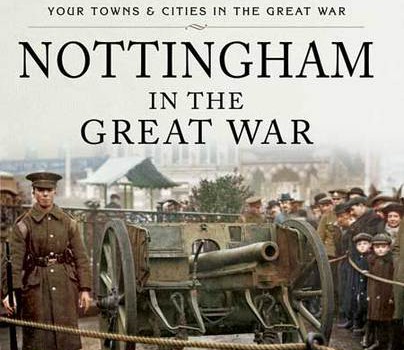

The publishers Pen & Sword have started a ‘Your towns and cities in the First World War’ series, in order to highlight just what those ‘at home’ had to handle. Carol Lovejoy Edwards has written the Nottingham volume, largely through sifting photographs from the Picture the Past Collection,[1] and then surrounding the images with an explanatory text divided into annual chapters 1914-1919.[2] It is written with a light touch, plenty of examples, many of which appear to be from newspapers although none are acknowledged, no great depth, and some occasional errors which suggest the author is not familiar with the city – where, for example, is or was the Southward Council School?

The home front was only partially involved with the actual day to day action on the Western Front because unlike the Second World War the threat from the air was as yet relatively limited. The problem for most families lay at home, not just in respect of sons and grandsons going to war, but also in terms of earning power, fund raising, work, and the occasional threat of a Zeppelin raid. At times food was also an issue, and some responses to war were distasteful in the extreme – notably the attitude to German-born people living peacefully (until August 1914) in the city. Other social changes included women moving into work, taking on roles such as tram conductresses, and shell filling – notably at the Chilwell depot which suffered a catastrophic explosion in July 1918.

What the book does not do is to offer any real depth of discussion. There is nothing on how families coped with separation, death and often serious injury to loved ones? And by stopping with the Armistice in November 1918, there is nothing on returning soldiers and the problems of reintegration, or of memorialisation, or of the impact of the war on the suffragette movement. Anyone who has been to the battlefields, or to the great memorials at Arras, Ypres, Verdun and elsewhere, knows that the war was a tragedy – a generation of young men wiped out, a whole society dreadfully aware of its loss, and a home front on which those left behind struggled to keep life going, and to respond to the call.

Nottingham had its military tribunals from 1916 with the introduction of conscription, and even a handful of conscientious objectors, but in general this was a war which the British accepted as a necessary response to German Imperialism. This book is too lightweight to do real justice to the way in which the people of Nottingham handled a conflict in which they were caught up, and which they felt, for the most part, compelled to accept for the greater good of the state and the Empire. Their job was to act as support for the war, and in general they did a remarkably good job.

[2] Carol Lovejoy Edwards, Nottingham in the Great War (Pen & Sword, 2015)

oad. On the left is a Czech cemetery, containing the remains of the Czech people who fought for France. The cemetery was constructed where the 2nd Battle of Artois took place, where the French and allied forces were trying to retake Vimy Ridge, which had been captured by the Germans in 1914 and provided clear views of the French positions. The area had been heavily fortified with a complex of tunnels, dugouts and machine gun posts – and was known as the Labyrinth.

oad. On the left is a Czech cemetery, containing the remains of the Czech people who fought for France. The cemetery was constructed where the 2nd Battle of Artois took place, where the French and allied forces were trying to retake Vimy Ridge, which had been captured by the Germans in 1914 and provided clear views of the French positions. The area had been heavily fortified with a complex of tunnels, dugouts and machine gun posts – and was known as the Labyrinth. The Czechs were in an unusual position at the outset of the war. Officially there were to fight for the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the side of the Germans, but many were trying to obtain independence for Czechoslovakia, so would rather fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the east many were captured by the Russians (sometimes voluntarily) and they formed the Czech Legion to fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the West, the Czechs who lived in France and elsewhere joined the Czech section of the French Foreign Legion in order to fight for independence. The first unit to fight for the French was the Nazdar Company, made up of 250 men. The name Nazdar comes from the unit’s battle cry, and means ‘Hi’. Eventually the number of Czech and Slovak soldiers came to 150,000 men who had volunteered from around the world. The initial men of the Nazdar company were the ones who fought on 9th May, assaulting and capturing a hill. Around 50 were killed, with another 20 dying of wounds.

The Czechs were in an unusual position at the outset of the war. Officially there were to fight for the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the side of the Germans, but many were trying to obtain independence for Czechoslovakia, so would rather fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the east many were captured by the Russians (sometimes voluntarily) and they formed the Czech Legion to fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the West, the Czechs who lived in France and elsewhere joined the Czech section of the French Foreign Legion in order to fight for independence. The first unit to fight for the French was the Nazdar Company, made up of 250 men. The name Nazdar comes from the unit’s battle cry, and means ‘Hi’. Eventually the number of Czech and Slovak soldiers came to 150,000 men who had volunteered from around the world. The initial men of the Nazdar company were the ones who fought on 9th May, assaulting and capturing a hill. Around 50 were killed, with another 20 dying of wounds. There is a Bohemian cross in the centre of the cemetery [cross image here] reminding the visitor of John of Luxembourg, the king of Bohemia, who died at the Battle of Crecy in 1346. He was blind at the time of the battle, and when he realised the battle was lost, he order two of his soldiers to lead him at the English, who killed him. There is also a monument at Crecy commemorating this suicidal act.

There is a Bohemian cross in the centre of the cemetery [cross image here] reminding the visitor of John of Luxembourg, the king of Bohemia, who died at the Battle of Crecy in 1346. He was blind at the time of the battle, and when he realised the battle was lost, he order two of his soldiers to lead him at the English, who killed him. There is also a monument at Crecy commemorating this suicidal act.