The Christmas Truces are among the most celebrated events of the First World War. But what did they mean to the men who observed them?

As we have discussed before, the question of the Christmas Truces on the Western Front in 1914 is a vexed one. Although truces and ‘fraternisation’ are a matter of historical fact, they have been mythologised and turned intro material for ceremony, advertising and jokes. It’s easy to see why. The truces, symbolic of common humanity amid chaos and destruction, make for stories that are at once heartwarming and heartbreaking. But can they be more than that? It is to be hoped that they can and that this compelling phenomenon might prompt people to question the nature of war in general and this war in particular.

The truces certainly prompted questions back in 1914 and gave its participants cause to question what they were doing in the trenches, what their opposite numbers were doing and what they had both been told.

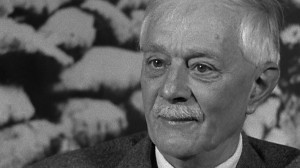

One of the highlights of the BBC’s Great War interviews, conducted in the early 1960s in advance of the half-centenary, is the series of anecdotes by Henry Williamson, who was in 1914, serving at the rank of Private in the London Regiment. At Christmastime 1914, he and his comrades were sent into no man’s land to hammer in some stakes to secure a key position. They were fifty yards from the German lines and, fearful of machine gun fire, began their sortie by crawling across the frozen ground. As time went on, they noticed that no gun fire came and they could walk freely on two legs, laughing and talking. ‘And then’, according to Henry ‘about eleven o’clock, I saw a Christmas tree going up on the German trenches. And there was a light’.

http://youtu.be/dUA8DSkSmBE?t=54m44s

The British soldiers approached the barbed wire which had been strung with empty bully beef tins so that it would rattle if a man drew near. Very soon they were exchanging gifts with the Germans. Smoking, talking and shaking hands, they swapped addresses so that we could write to one another after the war. And then they stopped to bury their dead.

The Germans used ration box wood to create makeshift memorials for their fallen comrades and offered a few words. ‘Für das Vaterland und Freiheit’, [For the Fatherland and freedom]. Williamson stopped him there. ‘How can you be fighting for freedom?’ he asked. ‘You started the war and we are fighting for freedom’.

‘Excuse me, English comrade’, replied the German. ‘But we are fighting for freedom’.

‘And here, you’ve put “Hier ruht in Gott” [Here rest in God]. ‘Yes,’ said the German,’ God in on our side’

‘But he is on our side’ replied Williamson.

That was, according to Williamson, a tremendous shock. ‘Here were these chaps, who were like ourselves, whom we liked and who felt about the war as we did, who said would be over soon because they [the Germans] would win in Russia and we said no, the Russian steamroller is going to win in Russia’

‘Well, English comrade’, replied the German ‘do not let us quarrel on Christmas Day.’

And quarrel they did not. Very soon, of course, both sides received stern orders to cease their fraternising and get back to their own trenches. But when the German machine guns resumed their fusillade, they were fired deliberately high and the British were advised to keep under cover in case ‘regrettable accidents’ happened. The truce, however, was over.

Henry William Williamson 1st December 1895-13th August 1977

Merry Christmas everyone.

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

ouching without being sentimental

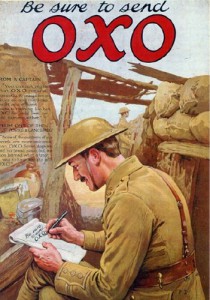

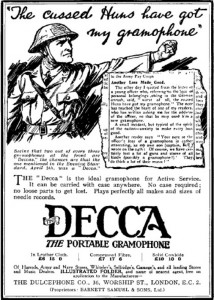

ouching without being sentimental ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.

ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.