The Sherwood Foresters in Dublin, Easter Week 1916

Nottingham Lakeside 7 October 2017

The Centre for Hidden Histories has provided financial support for a public engagement partnership examining the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916 and, in particular, the role of the 7th and 8th Reserve Battalion Sherwood Foresters. The battalion was mainly made up of young working-class men from Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire.

The subject has been researched in some detail by Professor James Moran of the University of Nottingham’s School of English, and he has also forged the public engagement programme with Hall Park Academy, Eastwood. Jim Moran has worked on the project with Professor Fintan Cullen of the University’s Department of History of Art. Fintan is from Dublin.

The Sherwood Foresters who were sent to Dublin had little idea of what they were walking into, and the battalion suffered the greatest casualties of all the British regiments involved in the insurrection. The soldiers were also made to participate in the firing squads that executed the rebel leaders. Jim and Fintan have researched the story of what happened both during Easter week and immediately afterwards when they were moved to Galway. They used archival material to explore how, at the time of the rebellion, the Sherwood Foresters believed that they would be remembered.

Much of the research was embedded in a specially devised performance at Lakeside by year 10 students from Hall Park Academy in Eastwood. The intention was to recover the voices of the soldiers from Nottinghamshire, and the play used the words of the soldiers, their opponents, and Eastwood’s most celebrated son D.H. Lawrence who, the audience was reminded, was not a conscientious objector but was found (on three occasions) to be unfit to serve on the front line.

Jim Moran introduced the play, in order to set the scene for the performance. The Second Battalion of the Notts and Derbyshire Regiment, better known as the ‘Sherwood Foresters’, were the last of the 1914-1918 war volunteers. They went to war to defeat the Germans but soon found themselves in combat on the streets of Dublin. The Foresters arrived in the Irish capital on 26 April 1916. They marched from Kingstown port (now Dun Laoghaire) into the city. The battalion was divided into two. Two thousand troops were sent into the city along the tree-lined Northumberland Road, cheered on by many of the citizens of Dublin – although some of the soldiers appear to have thought they were in France and were surprised to be greeted by cheering crowds speaking in English rather than French!

Far from having an easy ride against what they had been assured was an ill-disciplined and poorly trained rebel force, they found themselves up against well organised fighters, and within hours of their arrival more than 220 Foresters had been killed or wounded by just 17 men of the Irish Volunteers.

The Foresters had received just 12 weeks training, and they were ill-prepared for combat; indeed, some of the men had not even learned to fire a rifle. Their machine guns and hand grenades had been left on the dockside in Liverpool. The British military leaders believed that a show of force would be enough to end the uprising. It was a serious miscalculation.

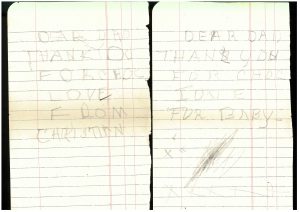

One of the officers leading the men was Nottingham barrister Christian “Freddie” Dietrichsen, a Captain in the regiment. Before the war, Dietrichsen – who was of Danish extraction, hence the surname – had married an Irish women, Beatrice Mitchell. They settled in Nottingham’s Park estate but with the outbreak of the war Freddie, fearing the possible impact of Zeppelin raids, sent his wife and children to Watford. Unbeknown to Freddie, Beatrice decided this was still too close to the action, and moved with her children to Dublin. They were among the crowd waving flags on Northumberland Avenue when Freddie marched past. He was surprised, because he thought they were in Watford, and they were surprised because they thought he was in France. The march into Dublin stopped briefly for Freddie to kiss his wife and children before carrying on. Shortly afterwards he was killed by a sniper’s bullet. In his jacket pocket were letters to him from his children, and a letter he had written but not sent, to his wife.

All of this was recounted in the Hall Park Academy’s performance at Lakeside, together with appropriate quotations from Lawrence. For the pupils, this was their first opportunity to perform on a public stage, for the parents it was an opportunity to be proud of their offspring, and for the Centre for Hidden Histories and Jim Moran it was an opportunity to find out more about a First World War event which the British army chose (presumably from embarrassment at having underestimated the Irish rebels) to play down. But, first and foremost, congratulations to the pupils of Hall Park Academy.