Contribute to a lively exchange of ideas at this three-day event at The National Archives

8-10 September 2016

This three-day conference will examine the Home Front during the First World War. It will look at those who were left behind, and explore life and society in the immediate aftermath of the war.

The conference will bring together academics, independent researchers, community groups and museum curators, among others, to generate dynamic discussion and networking opportunities. The event provides an opportunity for delegates to showcase recent research, foster new collaborations across the country and between different groups of researchers.

The conference is organised by The National Archives and the Everyday Lives in War Engagement Centre, on behalf of the five national World War One Engagement Centres funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

We welcome contributions from researchers working on the topics listed below.

Themes

The conference will explore four major themes:

- Life on the home front(s)

We are looking for contributions with an international as well as a British angle. - Dissent

As well as conscientious objection and political agitation, we also want the conference to explore the subtleties of dissent socially, religiously, and culturally. - Aftermath

We want to explore such issues as cultural memory, as well as immediate matters such as post-war riots, gender relations, food, and housing. - The unfamiliar

We are interested in exploring the less well-known aspects of dissent and everyday life, including the value of little-used sources and the interpretation of unusual artefacts associated with the First World War.

We encourage proposals that speak to one of these themes from the perspective of any geographical location. Potential topics include, but are not limited to,

- Political

- MI5 workers

- Radical political activism

- Government responses to dissent

- Female suffrage

- Workers’ rights/unionism

- Religious

- Spiritualism

- Christian Science responses to war

- Prophecy

- Religious pacifism

- Social and cultural

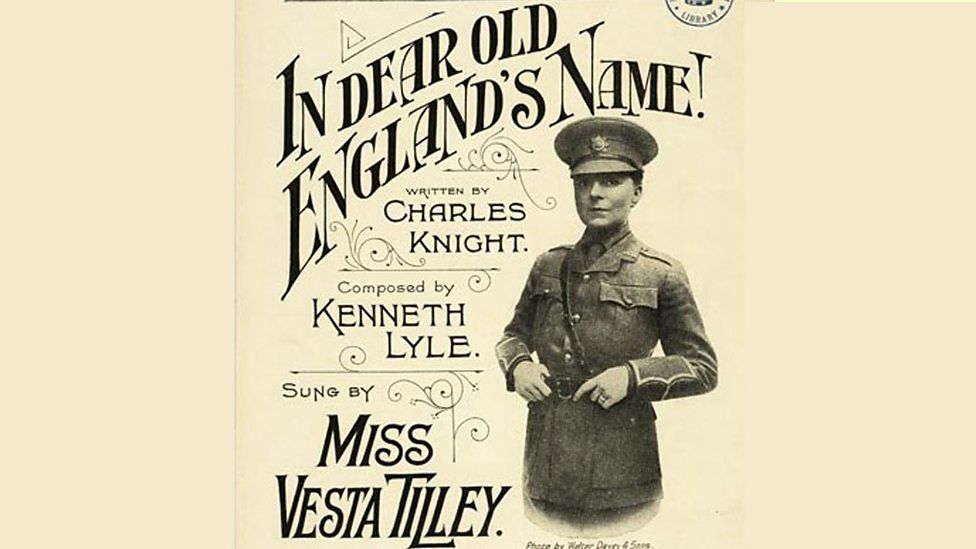

- Theatre and entertainment

- Disorder – e.g. food riots in 1919 – Luton Town Hall burned down.

- Profiteering

- Hoarding

- Problems with First World War pensions

- Fortune-telling

- Advertising

- Newspaper reportage

- Alien, prisoner and refugee life

- Comedy/satire (music hall, literary, cartoons etc)

- Gender

- Fashion (men and women)

- Female suffrage

- Female farm and factory work

- Children and role modelling (male and female)

- Choosing motherhood and non-childbearing lives in war and after

- Material culture

- Graffiti

- Pension records

- Internment camp magazines

- Registration cards, Belgian refugees

- School logbooks

- Photography

- Food

- Marketing and advertising

Format

We invite proposals for presentations that take the form of group discussions, workshops, 20-minute talks, performances, or posters. Guidelines and a workshop on creating an effecti

ve poster will be offered in advance for those considering this format.

Interested in participating?

We accept applications from individuals (whom we will then match to others working on similar topics), and from groups who wish to propose their own panel and involve relevant academics. We invite academics to present with independent and community group researchers. No affiliation to an academic institution is required to submit an application.

Please send a brief description of no more than 300 words outlining the topic you wish to share and your preferred format of presentation (i.e. round-table, talk, workshop, performance or poster).

Closing Date: 15 October 2015

Proposals should be emailed to: firstworldwar@herts.ac.uk

Enquiries can be directed to: Owen Davies, The University of Hertfordshire or Jessamy Carlson, The National Archives

Interested in attending?

Tickets will be on sale from early 2016

oad. On the left is a Czech cemetery, containing the remains of the Czech people who fought for France. The cemetery was constructed where the 2nd Battle of Artois took place, where the French and allied forces were trying to retake Vimy Ridge, which had been captured by the Germans in 1914 and provided clear views of the French positions. The area had been heavily fortified with a complex of tunnels, dugouts and machine gun posts – and was known as the Labyrinth.

oad. On the left is a Czech cemetery, containing the remains of the Czech people who fought for France. The cemetery was constructed where the 2nd Battle of Artois took place, where the French and allied forces were trying to retake Vimy Ridge, which had been captured by the Germans in 1914 and provided clear views of the French positions. The area had been heavily fortified with a complex of tunnels, dugouts and machine gun posts – and was known as the Labyrinth. The Czechs were in an unusual position at the outset of the war. Officially there were to fight for the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the side of the Germans, but many were trying to obtain independence for Czechoslovakia, so would rather fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the east many were captured by the Russians (sometimes voluntarily) and they formed the Czech Legion to fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the West, the Czechs who lived in France and elsewhere joined the Czech section of the French Foreign Legion in order to fight for independence. The first unit to fight for the French was the Nazdar Company, made up of 250 men. The name Nazdar comes from the unit’s battle cry, and means ‘Hi’. Eventually the number of Czech and Slovak soldiers came to 150,000 men who had volunteered from around the world. The initial men of the Nazdar company were the ones who fought on 9th May, assaulting and capturing a hill. Around 50 were killed, with another 20 dying of wounds.

The Czechs were in an unusual position at the outset of the war. Officially there were to fight for the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the side of the Germans, but many were trying to obtain independence for Czechoslovakia, so would rather fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the east many were captured by the Russians (sometimes voluntarily) and they formed the Czech Legion to fight against the Austro-Hungarians. In the West, the Czechs who lived in France and elsewhere joined the Czech section of the French Foreign Legion in order to fight for independence. The first unit to fight for the French was the Nazdar Company, made up of 250 men. The name Nazdar comes from the unit’s battle cry, and means ‘Hi’. Eventually the number of Czech and Slovak soldiers came to 150,000 men who had volunteered from around the world. The initial men of the Nazdar company were the ones who fought on 9th May, assaulting and capturing a hill. Around 50 were killed, with another 20 dying of wounds. There is a Bohemian cross in the centre of the cemetery [cross image here] reminding the visitor of John of Luxembourg, the king of Bohemia, who died at the Battle of Crecy in 1346. He was blind at the time of the battle, and when he realised the battle was lost, he order two of his soldiers to lead him at the English, who killed him. There is also a monument at Crecy commemorating this suicidal act.

There is a Bohemian cross in the centre of the cemetery [cross image here] reminding the visitor of John of Luxembourg, the king of Bohemia, who died at the Battle of Crecy in 1346. He was blind at the time of the battle, and when he realised the battle was lost, he order two of his soldiers to lead him at the English, who killed him. There is also a monument at Crecy commemorating this suicidal act.