Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

Michael looks at a new project that hopes to use football as a means of commemorating the first Christmas of the Great War…

It seems unlikely, given the state of no-man’s-land by December 1914, that anything like an organised football match took place during the Christmas truces. However, these spontaneous and cautious gestures did foster a handful of activities that may well have included a kick-about with a ball. It was then, as it is now, part of a universal language that demonstrates a similarity of outlook and reminds us that some things, class, fear, desire, football, remain the same no matter which direction your trench faces.

The existence of the Football Battalions, and the stories of professional players in the trenches offers a link to the past too. Young fans in 2014 can be encouraged to investigate the war by being reminded that, had they lived a century ago, the players they cheer on may well have ended up alongside them in uniform.

This is perhaps the thinking behind the Football Remembers project, run by the British Council, FA, Football League and Premier League. Starting on the 6th December, Football Remembers will encourage avid young historians and the footballing community to take part in a mass-participation event.

The scheme invites people to play a game of football, take pictures and share them via twitter with the hashtag #FootballRemembers. Any match of any size can be uploaded, from school to Sunday league fixtures, five-a-side matches to kick-abouts in the back garden. Teams in the Premier League, the Championship and FA Cup Second Round will also pose for group photographs before matches and will display them alongside these submitted pictures, as well as on a dedicated website.

In addition, the Premier League will hold a special edition of its annual Christmas Truce international tournament in Ypres, which it has staged for U12 footballers every year since 2011.

Special educational resources are available here and here to help with the planning of matches and, most importantly, for learning about the events of Christmas 1914.

ouching without being sentimental

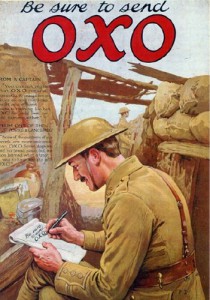

ouching without being sentimental ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.

ds such as Oxo, Bovril and Lea & Perrins were able to market themselves as being of use to soldiers on the front line, where nutritious hot drinks were no doubt very welcome indeed.