Movie portrayals of warfare can be very powerful, even when the war is not the central focus. Michael looks at an example from the 1990s

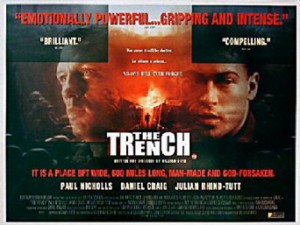

William Boyd’s 1999 film The Trench depicts a fusilier section during the 48 hours leading to the start of the Battle of the Somme.

The soldiers’ accents suggest a group drawn from different parts of the country, apparently in pairs with shared peacetime backgrounds. The putative lead, the Lancastrian Private Billy MacFarlane (Paul Nicholls) is partnered with his brother Eddie (Tam Williams) while a private dispute emerges on the part of the two Glaswegian soldiers over the issue of one’s clandestine engagement to a girl of their shared acquaintance. Lance Corporal Victor Dell (Danny Dyer) is a Cockney and Privates Ambrose (Ciaran McMenamin) and Rookwood (Cillian Murphy) Irishmen. Fusilier Colin Daventry (James D’Arcy) is evidently of a higher social class than his comrades and the likely beneficiary of a grammar school education (he has at least a smattering of German and has to pointedly moderate his latinate vocabulary to make himself understood even by his fellow Anglophones). He is, nevertheless socially inferior to the naive section commander, Second Lieutenant Ellis Harte (Julian Rhind-Tutt) who numbs his sense of being out of his depth with repeated slugs of whisky and private deferrals to his Sergeant, Telford Winter (Daniel Craig), the sole professional soldier in the unit.

The film’s action is almost entirely contained within the titular trench, creating an intentionally claustrophobic atmosphere that recalls a stage production. The young cast, mostly drawn from recent graduates of drama school is a reminder that the men who populated the trenches would, in other circumstances, be regarded as boys, a point emphasised by their scripted eagerness to participate in demonstrations of petty bravado, earning one lad a ‘blighty’ or in acts of barrack-room possessiveness over contraband photographs of nude girls.

Indeed, it is this matey comradeship (that includes minor rivalries) that is most impressive about this film. Take away the scenery and the uniforms and these lads could really be anywhere. Anywhere that raising your head too high might get you shot, that is. The effect of the scripting and the, let’s be honest, less than perfect nature of the performances (the young leads have all developed their acting skills since this film was made), lends The Trench a human quality that reminds us that the young men who fought in the real trenches were young, inexperience, scared and human.