Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

Community, Commemoration and the First World War

Here’s an interesting piece by University of Nottingham engineer Mike Fay on the development of the gas mask in the First World War.

John Beckett recounts the story of Thomas Porteous Black, the Registrar of University College Nottingham, who fought at Gallipoli.

The commemoration on 25 April 2015 of the centenary of Gallipoli, reminds us that white British casualties were found in places other than the trenches of the Western Front. The conflict itself is often viewed as being about the Australian and New Zealand troops, who went into action in Europe for the first time. ‘The ordeal of courageous Anzac troops under the command of bungling British generals has become the stuff of legend’ according to The Times (25 April 2015). By contrast, Britain has not made a great deal of the campaign, which was seen as botched, primarily by Winston Churchill, who had seen it as a way of opening a new front in the Eastern Mediterranean. Britain sent a 75,000 strong Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, which included British, Irish, French, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. By August 1915 the situation was dire, with troops pinned down in a bloody stalemate, having failed to move further than three or four miles inland.

Among the casualties was Thomas Porteous Black. A native of Aberdeen, but brought up in Darlington, Black was killed at Suvla Bay on 9 August 1915, as the 9th Sherwood Foresters were ordered forward against Turkish lines near Hetman Char in the Dardanelles.

Black’s death had a particular impact on Nottingham University College because he held the position of Registrar, at that time the senior administrator of the institution. He had joined the College as a lecturer in Physics, and had been appointed Registrar in 1911. As an officer in the OTC (Officer Training Corps), he quickly became involved in the war effort, and when the war started he joined up as a Sherwood Forester. As with all of the young men who died, and who had some form of association with the College, his loss was reported to both Senate and Council and, as ever, letters of condolence were sent to his family. He is also named on the university’s war memorial in the Trent Building.

In Black’s case the College decided to go further and to create a scholarship fund ‘to be awarded for research and to bear his name’. A circular letter dated 20 November 1915 and signed by the College vice principal Frank Granger and by E Lawrence Manning, described as honorary secretaries and treasurers for the Black memorial award, recalled how, as registrar, he had ‘carried out duties of special responsibility with an energy, foresight and tact, which was of great value to the numerous students who entered the College during his term of office.’

The letter continued: ‘It is hoped to raise a sum of £300 with a view to establishing a scholarship to be awarded for research and to bear his name.’ More than £50 had already been donated, including £10 10s from Principal Heaton, and £5 5s from his wife. A concert was held on 25 March 1916 to raise money towards the Black Memorial Fund.

By that time the ill-fated campaign in the Dardanelles was over. The Commander-in-Chief, General Ian Hamilton was recalled in October, and an evacuation began in December, which ended on 9 January 1916.

Like many people, I first heard And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda, from the mouth of Shane MacGowan as the final track on the Pogues’ 1985 album Rum, Sodomy and the Lash. It was a moving closer and a perfect fit for a record chock-full of classic folk songs both old and new. The only thing that struck me as odd about the song was the sheer volume of Australian references coming from an Anglo-Irish band. Of course, And The Band Played Waltzing Matilda wasn’t originally a Pogues song anyway. But nor was it written by an Australian.

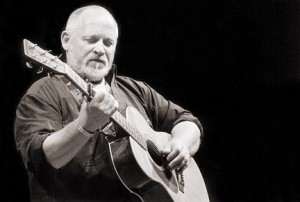

Eric Bogle was born in Peebles, in the Scottish Borders, in 1944. He began writing and performing folk songs while living in Scotland and continued to do so after emigrating to Australia in 1969 where he earned a living as an accountant.

In 1971 Bogle saw an Anzac march for the first time, an event that, according to the singer ‘was not as well attended or accepted as it is now’. Back then, veterans of the Gallipoli campaign were still alive to participate in the parade but Bogle’s mind was drawn to the then-current conflict in Vietnam. Motivated to write an anti-war song, Bogle nevertheless chose to portray the events of 1915 as they loomed larger in the Australian mind. Besides, as Bogle points out, ‘it doesn’t matter what war you’re writing about – the end result is exactly the bloody same: lots of dead young blokes.’

Bogle’s song, a first person biographical narrative that takes its character from living ‘the free life of a rover’ to the bloodstained sand and water of Gallipoli then back to Australia, maimed and forgotten, is a deliberate riposte to the romanticising of warfare. The protagonist is a young man who gets old very quickly and who ultimately cannot work out what the April crowds are marching for and who describes his fellow veterans as ‘the forgotten heroes of a forgotten war’.

This may have seemed likely in the early 1970s but in the decades that followed, Anzac Day, like its counterpart memorials in the UK, has grown in popular resonance. Now, in the centenary period, the Australian government will spend A$145m on commemorating the Australian involvement in the war. This weekend, 50,000 people are expected to attend the Dawn Service at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra while a service at Gallipoli itself will involve 10,500 people. In addition, a commemorative Red Poppy A$2 coin has been issued by the national mint. As with any aspect of the centenary, criticism and controversy are also in attendance, with some commentators complaining of ‘Anzac fatigue’ and others critical of attempts to commercialise the event.

Whatever your opinion of Anzac Day in 2015 -or any other year- what is certain is that it will not pass forgotten. Whether you intend to participate in a mass memorial event or just quietly consider the events of a century ago, you might find time to listen to the story of a fictional combatant performed in a song that also persists in the memory.

Here’s Eric Bogle…