On 13th June 2016, 25 year six students and their teachers from Grassmoor School in Derbyshire spent the day at the University of Nottingham learning about the First World War and being introduced to digital technology for young historians.

The Living Memory project

The Living Memory project is offering funding and resources to community groups across the UK to enable them to discover war graves in their local community, explore the sites and remember those buried there.

The Living Memory project remembers the forgotten front – the 300,000 war graves or commemorations right here in the UK.

On the centenary of the Battle of the Somme the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), in partnership with Big Ideas Company, is asking the public in the British Isles to re-connect with the war dead buried in their own communities.

This project is looking at the full 141 days of the battle of the Somme July 1 to November 18. We are looking to have 141 different community engagement events, reflecting the full length of that battle and centred on at least 141 different CWGC sites.

In total, CWGC has graves located in 13,000 locations, 200 of which are major sites and almost all in big city cemeteries and linked to the hospitals. The majority of men and women buried or commemorated either died in a British hospital of injuries sustained during the war or (in 1918-19) died in the influenza epidemic. They must not be forgotten.

CWGC have produced resources to help community groups identify a CWGC site near them, do some research about some of those buried in that site and stage a commemorative event – in their own way and reflecting their own interests – to remember those who lost their lives in the 141 days of the Somme.

To enable community groups to take part, funding, resources and support will be available. Visit www.cwgclivingmemory.org or email livingmemory@cwgc.org

“A ‘bloody tale’, best ignored”: The East African Campaign 1914-1918

This is a guest blogpost by Richard Sneyd, whose father Robin Sneyd served with the Faridkot Sappers and Miners, recalling the Campaign in East Africa during the First World War.

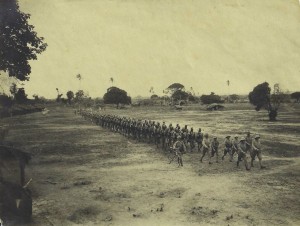

The Campaign in East Africa during the First World War was of a totally different kind to those on the Western Front, fought over immense distances without roads, over unexplored and unmapped areas, in deadly swamps and on remote mountains, in a tropical climate where malaria was rife. One of the more extraordinary aspects of this extraordinary campaign was the number of different ethnicities and cultures that were involved. Sikhs, Punjabis, Arabs, West Indians, Nigerians, Rhodesians and South Africans (both black and white), Sudanese, and members of many East African tribes fought side by side in the Allies’ comparatively small army. The contribution and suffering of these people, few of whom were defending their own land, has been explored by historians such as Hugh Strachan, Anne Sansom and Ross Anderson, but the Campaign is sometimes overlooked in popular memory of the First World War.

The War Office in London in August 1914, pre-occupied with sending the British Expeditionary Force to France, initially passed the responsibility for providing troops for any East African campaign to the India Office and through them to the Indian Army. General Barrow of the India Office in London assumed general control of Indian Expeditionary Force B. Against advice, the General changed the objective of this Expeditionary Force from just destroying the ports at Dar-es- Salaam and Tanga to bringing the whole of German East Africa under British Authority.

The General had greatly overestimated the capabilities of the Indian Army and the newly formed Imperial Service Corps from the Princely States. Neither Force had been trained for large scale expeditionary warfare outside India and were woefully short of machine guns and other equipment. Their role had been to control local uprisings. The Generals were inexperienced in commanding Indian troops outside India.

Early in 1914 Colonel Paul von Lettow –Vorbeck had been appointed Commander in Chief in German East Africa.(GEA) In August 1918 von Lettow had a small garrison known as the Schutztruppe of 2,600 German nationals and 2,472 African soldiers (Askaris) in 14 companies. His Askaris were loyal, well disciplined, well trained and well paid. In August 1914 the German Government and the Governor of GEA, Dr Heinrich von Schnee (although not Colonel Paul von Lettow) supported neutrality. Their offer to negotiate passed through the United States but did not reach the British until late September by which time it was too late to negotiate.

Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck realised that German East Africa would only be a sideshow with little support from Berlin so his policy was to try and avoid confrontation, keeping ahead of the Allied Forces leading them into the remote and disease ridden country where disease and malnutrition would kill and tie down many Allied troops, keeping them away from the Western Front and other battle fronts. This policy succeeded in that it maintained a campaign without putting too much of a demand on Germany for additional resources. Military action killed and maimed far fewer troops and porters than were lost to disease and malnutrition. German East Africa became a battleground imposed on the local population who were largely unaware of this remote quarrel between the Europeans. However, it was a strategic failure in the sense that it never diverted much in the way of British men and material from the Western Front itself.

The terrain and climate of East Africa made this campaign very different to the experience of the Western Front. The deadly tsetse fly prevented the use of draft animals or mounted infantry. Motor cars and lorries were often found to be practically useless, owing to the lack of roads and the heavy rainfall. Local porters were regarded as the best available means of transporting supplies and ammunition along the supply lines of communication which were sometimes up to three hundred miles long.

Hundreds of thousands of porters were employed and requisitioned by both sides. Their absence removed a vital part of the village work force, crops failed to be sown and harvested. The villagers’ crops and herds were further depleted by the Germans who lived off the country and operated a scorched earth policy. The Allies had to sometimes live off the land, their food supplies were further depleted by the Germans leaving behind German civilians, the sick and wounded, trusting that the Allies would look after them.

After decisively defeating Indian Expeditionary Force (B) at the Battle of Tanga in November 1914 Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck spent until early 1916 sending patrols into British East Africa as far as the Uganda Railway. In January 1918 the South African Lieutenant General Jan Smuts, who had fought the British in the Boer War, was appointed as Commander in Chief in East Africa and briefed to take his Forces on to the offensive by invading German East Africa. In March, Smuts led the invasion into the Moshi area of northern German East Africa. Smuts’ move prompted Colonel von Lettow to start his retreat through German East Africa, Portuguese East Africa, back into German East Africa, finally surrendering at Abercorn in Northern Rhodesia to General Edwards at 12 noon on 25th November 1918.

My father, Robin Sneyd, was a civil engineer and member of the Indian Army Reserve of Officers attached to the Faridkot Sappers and Miners as a Special Services Officer. The Faridkots were an Indian unit of about 150 men raised and paid for by the Raja of Faridkot a princely State in the Punjab. They were commanded by an Indian Lieutenant Colonel. The ethnic composition of the Faridkots was about 93% Jut Sikh with the remainder being Punjabi Muslims. European Special Services Officers of the rank of Major and below were attached to the Faridkots to give technical advice and liaise with others. The Faridkot Sappers and Miners were out in East Africa, longer than any other unit, working through the rainy seasons, repairing and maintaining roads and bridges.

Robin Sneyd left an extensive collection of notes, diaries and letters relating to his experiences in East Africa. I have compiled these records into a detailed account of the whole period of the Campaign, following the story of the Faridkot Sappers and Miners. The full text can be downloaded from The Great War in Africa Association website. I hope that my father’s story will raise the profile of this important element of First World War history and play a part in ensuring that those of all nationalities who were involved in the East Africa Campaign are acknowledged during the centenary commemorations.

Title quote: Edward Paice, ‘How The Great War Razed East Africa’, 4 August 2015, http://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/publications/how-the-great-war-razed-east-africa/