This is a guest blog by Pratap Chhetri

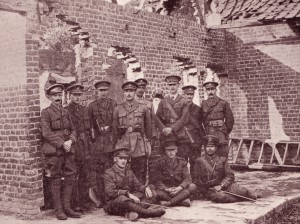

2014 marked the centennial year of the start of World War I or the Great War, as it is known. Across the globe from London to Auckland commemorative functions are being held to honour the memory of the brave and valiant soldiers who fought in the First World War and gave their lives for the humanity. These commemorations will last till 2018. Of late India too has geared up and started recalling the supreme sacrifices of its soldiers. This is a part of history we, as a nation should all take pride in – lest we forget.

India and the Great War

Undivided India’s participation numbered more than 900,000 combatants and 600,000 non-combatants in the War. More than 70,000 soldiers died on the battle front in various theatres of the war – France, Turkey and Mesoptamia, earning 9200 decorations which among others included 12 Victoria Crosses. Yet the Indian narrative remains largely untold and forgotten. Western academics and historians have always dealt with the Great War as a ‘white-man’s narrative’ forgetting the significant contributions of ‘the non-whites’ in the War. On the other hand, India has also shied away from taking credit and trumpeting its contribution because the War was fought for imperial defence under British colonial yoke. Whatever be the stance, the fact remains that India’s contribution was overwhelming. Indians fought right from the start to almost the finish. It was the first time in India’s history that soldiers of the Raj, Imperial Defence troops of Indian states, auxiliaries and labour force from all corners of the country – North, South, East and West and even from North East India participated in the War which changed the course of the world.

North East India’s Contribution to World War I

For millions from the modern world, the Great War that lasted from 1914 to 1918 was a theatre of sorrow and grief. But for the thousands of men who went to serve as paid volunteer labourers as a part of the Indian Labour Corps during 1917-18 in France on the Western Front from the then primitive North East India – a region that had been annexed by the British just a few decades prior to the start of the War; it was an epic journey of adventure and discovery into a hitherto unknown world. For these tribal men who had never seen modern civilization and whose contacts with the outside world were very limited, the War was a blessed opportunity that opened the horizons of their world enlightening them and the societies, they came from. The War acted as a catalyst that hastened the advent of modern civilization and aided the growth of education and spread of Christianity in faraway North East India. Most important of all, political consciousness began to slowly dawn amongst the Nagas, Khasis, Garo and Lushais as a result of their first exposure to modern civilization, thanks to this global conflict.

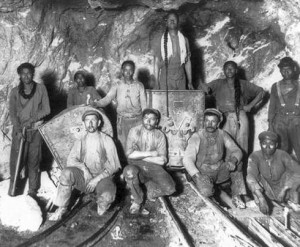

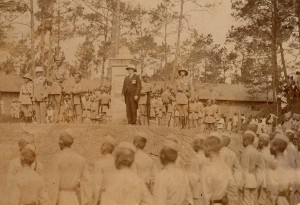

Men from present day North East India were a part of the 21,000 strong Indian Labour Corps who were recruited by the British from the non-martial races and tribals of present day Eastern and North Eastern India in early 1917 to serve as labourers and porters in the theatres of the action in France on the Western Front. These Labour Corps were christened from the regions that they came from – Garo Labour Corps, Khasi Labour Corps, Lushai Labour Corps, Manipuri Labour Corps, Naga Labour Corps and even the Chin Labour Corps from today’s Chin state of Myanmar, which was then still a part of British India. Each of the Labour Corps had a number of units. Each corps unit was roughly made of 500 men commanded by British officers and even sometimes by men who had worked in the region in various capacities but with little military experience. In some cases these officers were assisted by British missionaries who were spreading the Gospel in various corners of the then excluded areas of the north eastern part of India. These missionaries performed an important role – that of interpreters as these men would not have understood English and also acted as chaplains for the early converts.

Who were these men? Why did they go to fight for the British who had launched punitive mission against various tribes? What did they do? How did they adapt to their new vocation? What adventures did they meet with? These are some questions that arouse curiosity. Answers to these pertinent questions will require a lot of scholarly research. This article is a humble attempt to chronicle the origins and journeys of the various Labour Corps from the North East on whom war service as labourers was thrust by force, rather than by free will and choice.

Backdrop

By late 1915, the British War Committee, later known as the War Cabinet realized that shortage of labour might cost them dearly in the Western Front in France. As the War progressed, combatants could not be spared for non-combat roles. Unskilled labour was found to be needed for building roads and laying railway tracks, handling ammunition, docks, supply and storms depots, forestry, quarries, hutting, trench building and grave digging. Since the demand for labour could not be met from ‘the home turf’, it had to be imported from the British colonies abroad and even from China.

In January 1917, the Secretary of State for India wrote to the Viceroy asking if India could supply labour for the Western Front in France. While the big provinces such as Punjab, United Provinces, Madras, Bombay and others were already drafting and had sent soldiers in great numbers, the onus of providing labour fell on Assam, Bengal, Orissa and the North Western Frontier Province, who were not much represented in the British Indian Army.

The Assam Administration through the Chief Commissioner Archdale Earle responded saying that ‘eight to ten thousand able bodied hill men’ would be recruited for France. In Assam, amongst the tribal areas that were under British administration there was already an administrative and tributary structure in place through which demands for collies for portering and road building and even for expeditionary and punitive missions were regularly placed to the tribal chiefs by the Administration. It was perhaps this policy that the Chief Commissioner might have counted upon to generate the numbers1.

The Labour Corps was the organization that provided essential services to the army such as cooking, laundry, moving supplies and stores, burying the dead, unloading ships and trains and repairing roads and railways. Many of the Labour Corps’ worked far behind the frontlines but Indian labourers were often used for more dangerous work close to the action such as building fortifications or moving ammunition.

Lushai Labour Corps

The Lushai Labour Corps was initially called the 27th Lushai Labour Corps but it seems this Crops was later split up and numbered as – 26th, 27th, 28th and 29th Lushai Labour Companies. Around 2100 Lushais (Mizos now) left Aijal(Aizawl now); of which around 425 were from South Lushai Hills. They reached Marseilles in June 1917 and worked on fortifications, charcoal making and other taxing tasks. The corps was commanded by Lt. Col. Playfair. Rev.D. E. Jones ‘Zosaphluia’, one of the pioneer missionaries of the Welsh Mission in the Lushai Hills also was a part of the Corps. At the end of their service many were invited to visit Wales but none were prepared to prolong their stay in Europe. After more than a year on the frontline, the Corps headed back home in May 1918 and reached Lushai Hills in June 1918. 71 men perished the majority of who were war casualties. The names of these men are inscribed in the War Memorial in the heart of Aizawl. Every year on 7th December, Armed Forces Flag Day, wreaths are laid and sacrifices of these men as well as others who laid down their lives in the Second World War and other post Independent operations are commemorated.

It is interesting to note that in 1915 two years prior to the birth of the Lushai Labour Corps, a group of 30 young Lushais, somehow joined the 8th Army Bearer Corps and went to Mesopotamia. One among them was Lance Havildar Lalhema who received a Mention-in-Dispatches for his bravery and this commendation was signed by none other than Winston Churchill, who was at that time, the War Secretary. Seven of these men reportedly perished. Their names too, are inscribed on the War Memorial in Aizawl.

These men saw football being played for the first time and brought back the game to Mizoram. Till today, a particular variety of spinach which was brought from France goes by the name feren which means France. A popular folk song which was composed when the men left for France called ‘German Ral Run’ is still sung even today by Mizo youngsters.

Khasi Labour Corps

The Khasi Labour Corps initially seems to have been known as the 26th Khasi Labour Corps which was later divided into four companies – 22nd, 34th, 55th and 56th with perhaps maybe 500 men in each company. There seems to be no exact estimate of the number of men in this corps, or even if the numbers exists, it has not been reported in available literature on the subject. Herbert Cunningham Clougston and F B Wilkins were the European officers of the Corps while David Stephen Davies, a Presbyterian missionary and Rev. Shai Rabooh, a Khasi preacher also accompanied the Corps to France. 67 men died and to commemorate their sacrifices, a memorial ‘Mot Phran’ (which in Khasi means Stone from France) with the names of those who died inscribed on it was installed and inaugurated by the DC of Khasi-Jaintia Hills in 1924 at Iewduh in the heart of Shillong. Carved on the memorial is a quotation from the Roman lyrical poet Horace’s poem Odes : Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. (It is sweet and right to die for your country). The memorial still stands intact, though neglected over the years.

In 1915, the British Government ordered the expulsion of the German Catholic missionaries of the Congregation of the Divine Saviour (Salvatorians) who had set foot in the Khasi Hills in 1890. It was this congregation that laid the early foundations of the Catholic Church in the region and perhaps the North East too. The first Catholic Church in the North East was built by this Congregation in 1913 on the same site where the Cathedral of Mary Help of Christians stands today.

Garo Labour Corps

During April 1917, in reponse to the Deputy Commissioner’s call for enlistment in the Labour Corps, 1000 men were recruited from various places across Garo Hills. This corps was to be the 69th Garo Labour Company. The men were stationed in Tura for almost four months due to delay in receiving orders. During this period many of the recruits suffered from various diseases. By the time the Corps left Tura for France in August 1917, only about 500 of them were declared fit to move to France. Some of these recruits died enroute the long 5000 kilometre journey across the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea and the Mediterranean Sea and according to some records, only 456 of them reached France.

In May 1918, the Garos were allowed to return to their homeland. They arrived at Tura on July 16, 1918. As they were officially released at Gauhati, some of them got down here, some at Goalpara district stations and some at Garobadha while only 120 men actually arrived at Tura.

A total of 58 men died. One died while the recruits were still camping at Tura, one at Garden Reach, Calcutta, one on boarding the ship at Alexandria and 55 men in France. The names of these men find a place in the Cenotaph that was erected in Lower Bapupara in Tura to commemorate the Corps. The day of their return from France – 16th July is solemnly observed every year as a day of remembrance as the Garo Labour Corps Day.

By late April 1917, almost all the Labour Corps were released since their contract was only for a one year term but there seems to have been some re-organization of the remaining Indian Corps into four Companies and one of them was the 84th Garo Company. These four companies stayed on till the end of the War. It is not known definitely whether some men from the 69th Garo Labour Company stayed back and were a part of the new Company or simply it was an error of nomenclature.

Naga Labour Corps

Around 2000 Nagas – 1000 Semas, 400 Lothas, 200 Regmas, 200 Aos and 200 Changs and other Trans-frontier tribes seems to have been recruited and this group of men were designated as the 21st Naga Labour Corps. According to some written documents quoted in various books the 21st Naga Labour Corps arrived in France in two main groups (688 men on 21 June 1917 and 992 men on 2 July 1917). The Deputy Commissioner, Mr. H. C. Barnes went in command with a number of clerks and Dobashis(interpreters). It is presumed that more than 400 men perhaps were not found fit to sail for France. These men were initially divided into the 15th, 16th, 17th and 18th Naga Labour Companies. To avoid confusion with other Indian Labour Corps units serving in Mesopotamia at that time, these companies were renumbered as the 35th, 36th, 37th and 38th (Naga) Labour Companies. The men of the Naga Labour Corps worked in Mametz, Le Transloy, Haute Avesnes, Contalmaison and Guillemont on salvage work, road repairs among others. Another batch of 817 Naga Hills recruits which was waiting to go to France was diverted to the Kuki operations in January 1918. This draft consisted of 60 Lhotas, 90 Semas, 120 Aos, 60 Kukis and Kacha Nagas and 480 Angamis. There is no known Memorial in Nagaland to commemorate the men who died in France. But amongst all the tribes, the Nagas were the first to realize the need to organize and unite themselves. Men who returned from France formed a socio-political association called the Naga Club with branches in Kohima and Mokokchung immediately after their return in 1918. This was the association that later in 1928 sent a representation to the Simon Commission asking them the right of choice of self determination when the British left India.

Unfortunately during the Second World War in 1940, the building holding the lists of men of Labour Corps units was destroyed by Japanese bombings.

Manipur Labour Corps In early 1917, the Raja of Manipur Chura Chand Singh and the Political Agent Lt. Col. H.W.G. Cole sent official requisitions to all villages in the hill areas of Manipur to recruit men for the labour Corps. The villages were required to supply able bodied men in proportion to their population. Many of the villages were aghast at the idea of sending their men to unknown lands from where perhaps they might not return at all. But despite the fears of the people, about 2000 men were recruited for the 22nd Manipur Labour Corps which again like the rest of the other Corps was divided into four companies – 39th,40th,65th and 66th Manipur Labour Companies. The majority of men in the Manipur Labour Corps were Meiteis, Tangkhuls, Koms, Kukis. Angom Porom Singh, the first Meitei Christian and Porachao led the Meitei contingent; R. S. Ruichumhoa, one of the first educated among the Tangkhuls of Manipur and one of the early evangelists among the Western Tangkhuls led the 1200 strong Tangkhul contingent; Teba Kurong led the Kom contigent while Thomsong Ngulhoa, a Kuki Christian evangelist was the leader of the Kuki recruits. In 1916, the Raja of Manipur Sri Churachand Singh had offered to raise two detachments of men from the ranks of the State Military Police to aid the British in the War. 315 men who formed the Double Company underwent training with the 3/39th Garhwalis in Lansdowne before they were pressed into active service in Mesopotamia during 1917-18. The Double Company was under the command of the Mr. F. B. Blackie who was the Private Secretary to the Raja of Manipur. Churachand Singh visited these men in Lansdowne in February 1917 to bolster their spirits before they embarked on their arduous journey and dangerous duty. The Raja also made monetary contributions for the purchase of four motor ambulances and an aeroplane besides subscribing to the War Fund. In September 1917, when another requisition was placed for fresh labour drafts, the hill tribes especially the Kukis revolted and took up arms against the Raja and the British. This revolt known as the Kuki Rebellion (Uprising) of 1917-1919 or Zou-Gal was perhaps the largest ever uprising against the British in North East India by any tribe in the region.

Tripura

In 1917, King Birendrakishore Manikya offered one lakh rupees to the War Fund besides a annual contribution of Rs.15,000 annually during the continuance of the War. The Tripura Durbar also sent 800 shirts for the 11 Rajputs serving in Mesopotamia. At the request of the Munitions Board, the Tripura Durbar sent 23,000 bamboo for rivetment work in Mesopotamia. There was also an effort to obtain men for the Army and the Durbar offered a cash donation of Rs. 25 or a free grant of 6 bighas of land for those who enslisted from Tripura. In 1917, 17 men were recruited and in the course of the war about 40 men enlisted.

Hundreds of labourers were victims to long-range shelling, air raids, and enemy action during the German Spring Offensive in 1918. Illness claimed the lives of many more, particularly during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Many died on the long journey to France via foot, rail and ships.

The names of men who died during the War are inscribed in various Memorials such as Neuve Chapelle in France, Basra Memorial in Iraq and Heliopolis Memorial in Egypt and hundreds were buried in cemeteries across France such as Ayette Indian and Chinese Cemetery, Mazargues War Cemetery Marseilles, La Chapelette British and Indian Cemetery, Haute Avesnes British Cemetery, St. Sever Cemetery, Rouen, Blargies Communal Cemetery Extension and also at the Mala Cemetery in Yemen and at the Faenza Communal Cemetery in Italy.

References and Acknowledgements

- Radhika Singha. ‘The recruiter’s eye on “the primitive”: to France in the Indian Labour Corps, and back, 1917-1918’, in James Kitchen, Alisa Miller and Laura Rowe et. al., Other Fronts, Other Combatants, Cambridge Scholar Series, 2011, pp.199-223. (Acknowledgement for cited passage from the article)

- L.W. Shakespeare; History of the Assam Rifles

- J P Mills; The Ao Nagas, The Lotha Nagas and The Regma Nagas

- Khomdan Singh Lisam; Encyclopaedia Of Manipur (3 Vol.)

Postscript : Facts and figures on the various Labour Corps have been culled from a number of documents and books. Very often these records do not match. Readers are requested to share any information that they might have on the Labour Corps with the writer at prachhetri@gmail.com, for which the writer would be remain indebted; it could be pictures, books or even vernacular writings on the experiences of the members of the Labour Corps.

Financial barometer

Financial barometer