Like many universities, Nottingham was touched by the Great War. In this guest post, Emma Thorne looks at the story of one young man whose journey took him from Nottingham to the battlefields of Europe.

For almost 100 years, the name Captain Jacob Hardy Smith has been on permanent display on the marbled corridors of the University’s Trent Building. If you’re a member of staff or a student, chances are you’ve probably walked past it countless times without ever giving it a second glance.

Jacob is one of more than 200 officers and cadets from the University who gave their lives in service to their country during the First World War and whose sacrifice is commemorated in a special memorial plaque.

His name may have endured for almost a century but until recently it appeared that the details of Jacob’s life and heroic actions during the conflict, like those of his fellow servicemen, had been largely lost to history.University’s WW1 memorial plaque

That was until a chance enquiry to the University’s Centre for Hidden Histories led to Jacob being commemorated as part of an online initiative by the Imperial War Museum.

Prudie Robins, Jacob’s great niece got in touch with Michael Noble, Community Liaison Officer at the centre after discovering that Jacob had been a member of the Officer Training Corps (OTC) at University College Nottingham in April 1909 through an entry in the London Gazette.

Prudie, who lives in Lincolnshire, had been researching her family history in an effort to shed light on the story of her great uncle — her grandmother’s youngest brother — but the details were rather sketchy. However, she had discovered that Leicestershire-born Jacob, the son of a leather merchant, had joined the OTC at the University College Nottingham while studying the chemistry of tanning.

Researching the past

Michael Noble, Community Liaison Officer at the centre, was able to confirm that Jacob had been among the members of the college’s OTC and that his name is among those on the University’s First World War memorial. Colleague Professor John Beckett has been researching the OTC at University College as part of a wider history of The University of Nottingham which he is currently writing.

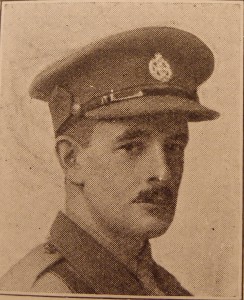

Even more excitingly, the academics were able to dig up some further information through the University’s Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections. Among the records related to the OTC were documents that made mention of Jacob Hardy Smith as a former OTC ‘old boy, done good’ — he got his commission into the Connaught Rangers, a regiment with affiliations to the Rifle Brigade, in 1914 and there is reference to the medals which he was awarded later in his career.Jacob Hardy Smith

Additionally, they uncovered a photograph of the OTC around the time when Jacob was a member, led by commanding officer Sam Trotman, although they were unable to identify his face among the crowd due to the quality of the image. Michael said:

“I sent a copy of the photograph to Prudie and she was delighted that we were able to confirm that there was a record of Jacob here. This started a dialogue between us and it was nice that we were able to support her in the research she had been doing into her own family history.”

Between them, they have been able to piece together the story of Jacob’s military service, starting with his training on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent as part of the 6th Battalion. Information from the Royal Green Jackets Museum shows he later joined the 3rd Battalion and was among the first wave of soldiers to arrive on French soil, landing on 10th September 1914, just over a month after Britain declared war on Germany.

An extract from the Rifle Brigade Chronicles reveals that Jacob led an attack on German trenches on the 25th September with great courage and determination and in which the Brits suffered heavy losses. The war record from the 3rd Battalion Rifle Brigade talks of how in October, 2nd Lieutenant JH Smith was mentioned in despatches and received the Military Cross for his part in the bold capture of an enemy officer in a separate skirmish.

Meritorious service

Jacob died in No 2 Stationary Hospital on the Somme on 29th August 1916 from serious wounds sustained through fighting two enemy officers in hand to hand combat at Guillemont — both of whom he killed — and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order medal posthumously for his meritorious service.Jacob’s medals.

In recommending him for the DSO, Jacob’s commanding Colonel wrote:

“He was the best Company Commander by far that I have seen out here. Absolutely fearless on all occasions, he was a very fine example of what an officer should be. He had trained his Company to perfection and the way in which his Company behaved, after all the officers had been hit, was entirely due to him.”

Prudie has since made a special visit to his grave in the Abbeville Communal Cemetery on the Somme and she honoured his memory by planting a ceramic poppy at the recent WW1 memorial at The Tower of London. Through her research she was even able to uncover distant cousins who she hadn’t known existed. A big moment was the discovery that they too had some cherished possessions belonging to Jacob — most notably his original medals which Prudie had feared lost.

“The research really took over my life,” she said. “It was like a giant jigsaw puzzle and it has taken me the length and breadth of the country chasing leads. I would spend hours scanning the internet before finding another potential clue and then off I’d go again.”

The Centre for Hidden Histories is part of a partnership with the Imperial War Museum, which has uploaded many thousands of records of those who served to a searchable online resource through an initiative called Lives of the First World War. The initial data was taken from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission but has now expanded to include records from other sources including the British Merchant Navy and the British Women’s Royal Air Force Service Records.

The idea behind the initiative is to preserve these old records for posterity and to champion the men and women who gave their lives during the First World War.

“It’s like Facebook for dead people,” Michael added irreverently. “You can also upload images and documents and it produces a personal timeline from birth to death. Importantly, it also encourages other people such as family members to get involved in remembering them and telling their story by uploading their own materials.”

Preserving the past for future generations

The centre has worked with the museum to promote the resource but also to test it and, with Prudie’s permission, Michael used Jacob Hardy Smith as a test case and means of exploring the effectiveness of the site.

Between them they have posted everything they could find about Jacob, including old family photographs, images of surviving artefacts belonging to Jacob including a pocket watch, an engraved silver wallet and moving letters that Jacob sent home to family from the trenches — in one he includes a touching hand drawn sketch of his dugout for his five-year-old niece Joan.Jacob’s drawing of his dugoutJacob’s pocket watch

Prudie has found the resource to be a fantastic way of ensuring that Jacob’s story is preserved for future generations of her family, while enjoying the ability to contribute to building a fuller picture of his life and gallant actions. She added:

“I would recommend this type of family research to anyone, it really has been quite an adventure. Before I began on this journey I really knew very little about my grandmother’s side of our family. Previously, Jacob had been little more than an anonymous face in a photograph and a small collection of his surviving possessions. Now I feel I know more of the man and can be proud to be a part of his family.”

If Jacob’s tale has inspired you to dig into your own family’s history, why not come along to the Centre for Hidden History’s free Family History Day on University Park campus on Tuesday July 21? The event will offer the opportunity to learn how to go about uncovering clues to your ancestry and researching your family tree. There will also be the chance for members of the public to use the University’s specialist technology to make high quality scans of their photographs and documents. Representatives of the Lives of the First World War project will be there encouraging people to use the site to remember their families.