The First World War had an impact on many large institutions and the University College, Nottingham was no different. John Beckett looks at the role played by the college in preparing young men for warfare.

The impact of the First World War on University College, Nottingham, was profound. By its very nature, an institution concerned with higher education was likely to have a large number of young men on its books, both as students and staff, in the appropriate age range to join the armed forces. In addition, the formation of the Officer Training Corps (OTC) had encouraged the notion even in peace time, that educated young men should be considered as potential military leaders in the event of war.

In 1906 Lord Haldane, the Secretary of State for War, appointed a committee to look into the problems caused by shortages of officers in the military reserve The committee recommended the formation of what became known as the OTC with a senior division in the universities, and a junior division, now the Combined Cadet Force, in public schools. University College Nottingham OTC was formed on 27 April 1909, following a petition signed by 27 students who were no doubt imbued with the patriotic ethos which underpinned the OTC. The Commanding Officer, from the beginning and throughout the war, was Captain Samuel R.T. Trotman, M.A., F.R.I.C.

The war broke out in the middle of the College’s summer break, but within a few days it was announced that it would provide facilities for the training of a limited number of young men in the theoretical and practical subjects required by the syllabus of the OTC examination. Applications were sought from those who intended to apply for commissions in the Special Reserve or the Territorial Force. In other words the College would adapt to provide the training required by potential officers.

All male students were eligible to volunteer. They enrolled in the O.T.C. as cadets and undertook theoretical and practical military training alongside their college studies. The training involved instructional parades, exercises and field operations, musketry, annual training at camp, lessons in tactics, map reading and military engineering. Student Cadets who passed an examination were entitled to a commission in the Reserves, or Territorial Force. Trotman rapidly built up the numbers and by 1913 he had 106 cadets. We know from his remarks at the November 1912 prize giving that he was a firm believer in preparing for war. As the historian Robert Mellors noted of Trotman,

‘he had travelled in Germany, and seen the preparations, and arrived at the conclusion that War was intended; he thereupon resolved that he would do all that one man could towards saving his country, and he did it’.

Trotman, born at Frome, Somerset, in 1869, had been Science master at the Nottingham Boys High School, where he had trained the Cadet Corps. From 1893 he was Nottingham City and Public Analyst, and having agreed to take on the OTC he found himself with two demanding tasks when the war broke out. To do them both, he rose at 4 a.m. to spend three hours in his laboratory before breakfast, he then went to Bulwell Hall to train recruits from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and frequently returned to his laboratory in the evening.

Initially the corps had its emergency headquarters at Trotman’s house in Lucknow Drive, Mapperley. This was then moved for a time to Bilbie Street, and each day the contingent marched out to Bulwell Common for training. Eventually Nottingham Corporation placed Bulwell Hall at its disposal, and those cadets who did not live in the vicinity were billeted there, under the personal supervision of Trotman and his wife who for some time lived in the hall and cared for their adopted family. Fortunately, Trotman’s wife appears to have been as committed to the cause as he was, and provided ‘motherly aid’ to the boys living at Bulwell Hall.

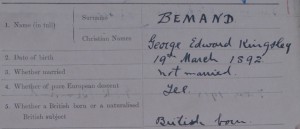

In total 103 Nottingham cadets had been gazetted to commissions by November 1914. Many of them, Trotman recalled, had enlisted ‘and in most cases obtained commissions very quickly’. By then one staff member, Captain Frederick Forster, and four senior officers with attachments to the unit, Major Charles Pack-Beresford, Major William Christie, Major Nigel Lysons and Lt Col Walter Loring, had fallen. On 24 November 1914 it was agreed to place a Roll of Honour in a prominent place for members of staff and students who had joined up.

These arrangements were formalised in December 1914 when a Department of Military Science was set up to teach the skills that officers would need in the war. Trotman was commissioned to prepare a course of study for students suitable to those studying for degrees and those seeking commissions. He told Council in December 1914 that Military Science would occupy three hours of lectures each week for map reading, military engineering, and practical work such as the ability to handle a company of infantry, advanced military science, special courses to meet national emergencies, and courses for those unable to undertake military duties. Trotman was given the position of Honorary Director of the department. Certificates of proficiency were granted, and special advantages were conferred upon the holders of the certificates. Various facilities were provided for shooting practice, including Miniature Ranges – Carrington Range (open air) 25 and 50 yards, and the High School Range 25 Yards – and the full range at Trent College:

‘A qualified Sergeant-Instructor is appointed, and every facility is offered to a cadet to become efficient. Uniform, equipment and ammunition are provided, so that membership entails no expense. All enquiries should be addressed to Capt S.R. Trotman, University College, Nottingham.’

Within a year ninety students had enrolled for the course, and by the end of 1915 365 students were attending classes in the Department of Military Science.

Special courses of lectures were delivered to officers, NCOs, and men of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Regiment and the RFA, stationed in Nottingham. Miss Hutchinson lectured on ‘The Health of the Soldier and Care of the Wounded’. Professor Kipping gave lectures on ‘Map Reading’, Mr A.H. Simpson on ‘Aids to Military Night Work’, Mr A Levi on ’The Care of the Horse’, and Professor Robinson on ‘The Motor Car in Battle’ – an indication of the overlap between old and new which marked the war.By the end of 1915, 748 former students and members of the OTC had joined the armed forces. Military Science was open to all students able to handle a company of infantry, and courses were on offer for those unable to undertake military duties, and by the end of 1915 special classes had been introduced for men wishing to obtain speedy commissions in the army and attended by 365 students.

In September 1915 members of the Citizens’ Army requested to be allowed to attend the evening classes on military science, but it was left to Trotman to decide whether or not this was feasible. The result was that lectures and practical instruction for officers of the Citizen Army were available from here until the end of the war. Lectures offered to members of the Citizen Army included Captain Trotman on ‘Tactics’, Professor Kipping on ‘Musketry’, and 2nd Lieut Mee on ‘Map Reading’.

Trotman’s work altered when in 1916 the government introduced conscription. A part-time military science course for boys under military age was introduced, together with a full-time military science course for boys approaching military age, and numerous other courses. Trotman later recalled: ‘we trained large numbers of “attested recruits” until their turn came to join up’, in other words they trained potential officers who enlisted when they were old enough: ‘We held classes for this purpose also in Mansfield both on weekdays and Sundays.’ He added that ‘for a considerable time the only rifles in Nottingham were those belonging to the O.T.C. and the rifle instructor which we were always willing to give to the Citizen Army and others was much appreciated’. Students of the Elementary Training Department who had joined the army under conscription were to have their entrance fee returned to them and advised that should they wish to return after the war they would be admitted for a further two terms without payment.

The form of education on offer changed again in 1917 when a new scheme was introduced allowing students wishing to train for commissions to attend instruction in the department of Military Science every morning, and Monday and Thursday afternoons additionally, and special classes on the other three afternoons. In October 1917 students doing Military Science were expected to attend Bulwell Hall on a Thursday and Saturday, and to wear uniform.

By 1918, 1,632 cadets had passed into the Army through the University College. They won five DSOs, 91 MCs, fourteen with bars, and several Croix de Guerre and other decorations, besides nearly 50 mentions in dispatches. More than 500 were wounded and 229 died. Some outstanding young officers graduated through the Nottingham OTC. Philip Johnson ‘personally brought back six machine guns’, while his sister Winifred left elementary school teaching in Nottingham to nurse on the Western Front. Frank Hind (19) died attempting the rescue of a comrade under heavy fire. Eustace Cattle ‘led a bombing attack under very difficult circumstances … crossing in the open to do so under close and heavy fire from enemy snipers’. William McClelland was described as ‘one of the bravest men in the line; Harry Beedham led a bayonet charge at Cambrai; Charles Vigors ‘showed great course and determination’ in repulsing an enemy attack in Salonika.

When, eventually, the war ended, there were numerous pieces to pick up: students who returned to complete their studies, frequently mixing with young men and women who had not played any direct role in the war; and new challenges in terms of the curriculum, arising from concerns which had arisen about Britain’s overall educational attainment.