Dr Jim Beach (The University of Northampton) and Joyce Hutton (Archivist) at the Military Intelligence Museum have been working with a team of volunteers associated with the intelligence services in order to excavate the ‘hidden history’ of the Intelligence Corps during World War One. So who were the Intelligence Corps and what was their role during the conflict?

From August 1914 the British army recruited a miscellany of individuals to its newly-formed Intelligence Corps. Drawing initially upon civilian linguists, the corps evolved from a small collection of well-meaning amateurs of variable quality to a large, well-structured, and professional organisation. By the Armistice its officers and men were shouldering the main weight of Britain’s intelligence work on the fighting fronts. But the Intelligence Corps in the First World War has been difficult for historians to research. Primarily this is because it was a temporary organisation, with the army deliberately omitting the corps – for security reasons – from key reference documents such as the Army Lists. This problem is further complicated by the fact that the corps constituted only one segment of the army’s intelligence personnel, so many doing intelligence work never belonged to it. Since the 1960s a number of historians have synthesised the corps’ history between 1914 and 1919, but this has usually been within the context of a broader ‘regimental’ history or general surveys of military intelligence.

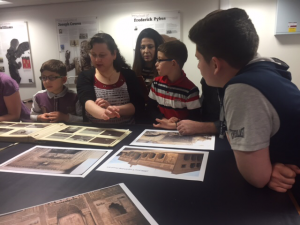

Funded by the Centre for Hidden Histories and Everyday Lives in War, the ‘Secret Soldiers’ project seeks to contribute a more comprehensive history of the role played by the Intelligence Corps in World War One. Key aims held by Jim, Joyce and the volunteers are to establish a more accurate estimate of the number of Intelligence Corps officers in this period and to have a more complete record of the organisation’s activities. Working with ex-Intelligence Corps volunteers on this project has allowed Jim to delve far deeper into this area of history than he thought possible. In an interview in September 2017, Jim noted that the former investigators who work on this project sometimes think through problems associated with the Military History Museum’s collection in a very particular way. For example, if the information cannot be found in one record set, the volunteers are often able to suggest another section of the archive where the information might be discovered. This is based on their administrative knowledge of how the Intelligence Corps works. In relation to this process, Jim has noted, “What they have shown…is that the information available is of an order that I didn’t think was possible…the depth and quality of the material is way beyond what I would have thought at the beginning.” For Joyce, the ‘Secret Soldiers’ project is an opportunity to excavate the archives, closely read documents and understand their value within the context of the Museum’s collection.

The Centre for Hidden Histories looks forward to reading the publications that are planned to arise from this fascinating collaboration. Click here to read about a recent ‘Secret Soldiers’ event held at the University of Northampton in December 2017.