The Centre’s Principal Investigator, Professor John Beckett, uncovers the story of a daring escape from Sutton Bonington, today one of the University of Nottingham’s UK campuses.

During the centenary commemorations of the First World War, The Times is running a daily column reprinting a war-related activity first covered one hundred years ago. On 26 September 2017 it reproduced a story from 26 September 1917 headed ‘Escape of 23 War Prisoners’. It was about the escape of German officers from the internment camp at Sutton Bonington.

The Times reported the story with a certain sardonic humour. The German POWs had dug a tunnel and collected supplies ready for the break out, but having escaped they then struggled to put much distance between themselves and the camp. Six of them were caught near Nottingham, two were found asleep in a wood ‘worn out by their walk’, and three were arrested when they aroused suspicion by asking the way to the nearest railway station. Captain Muller was caught when schoolchildren found him blackberrying in Tollerton woods, six miles from the camp. Two more were found in East Leake ‘playing at cards while crouching beneath a hedge’.

These two men do not seem to have been trying all that hard to make their way back home, and apparently confessed the whole story. The escapees had tunnelled a distance of 50 yards over a three months period. Having escaped they divided into groups of four and started out on different routes towards the coast ‘where they hoped to get away by tramp steamers’.

Eighteen of those who escaped had been recaptured by 28 September 1917, and four more were taken at Chesterfield by Derby police on 30 September.

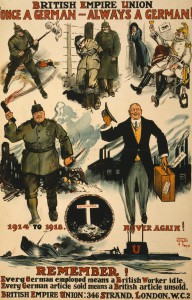

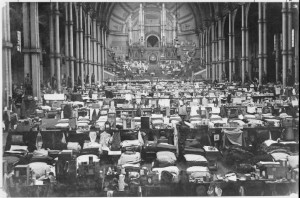

The story is, of course, well known. The Midland Agricultural College had been preparing to move from its premises in Kingston on Soar to the main building and men’s hostel newly built at Sutton Bonington. That building had a date stone of 1915. Before the move could take place the buildings were taken over to house German officers, who were generally well treated when they were captured as prisoners of war. In 1915 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle complained that they were quartered well away from ordinary soldiers, often in country houses or in the officers’ quarters of barracks. These were comfortably furnished, and servants were found for them from among the soldiers held as POWs. One of the prisoners, named in The Times, Captain Muller, had been in command of the Emden, a German raiding cruiser which had bombarded Madras in September 1914, and was subsequently sunk off the Cocos Islands on 9 November.

When the Sutton Bonington escape was reported, special constables were called out ‘and every measure was taken to apprehend the escaped prisoners’. With night patrols and road blocks, as well as special constables at strategic points, the prisoners were prevented from making much headway.

Lieutenants J. Stadelfaauer and P. Bastgem were recaptured in Derby after a week on the run – perhaps an inappropriate term since they had travelled just twelve miles from Sutton Bonington. Three men caught in West Bridgford on 25 September 1917 had among their possessions sardines, milk, bacon, ham, cheese, prunes, sausages, biscuits and dried toast. They might not have got far in their search for a packet boat to take them to Germany, but they were not going to starve. In fact, in the course of the First World War, only one German officer made it back home.