This week I had the pleasure of visiting the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester and of seeing the From Street to Trench exhibition that has been designed to reflect the contribution of, and effect on, the North West of the First World War.

As with many of the regional exhibitions, the focus is not merely on the local aspect of the war (which, for the North West means references to the Eccles cotton mill and the auxiliary hospital at Dunham Massey) but on the directly personal. Letters and artefacts, many of which have been donated or loaned by local people, tell the story through the eyes of the ordinary men, women and children who experienced the war at first hand. There is a paradoxically rich mundanity to these items. Their very ordinariness means that the war is set as a very loud background event to people’s lives. Examples such as the letter from some children, begging Lord Kitchener not to take their pony for war work, (he didn’t. The animal was too small for it), or the recorded testimony of Ernie Rhodes, who cheerfully recalled being promoted at work when some of the lads above him absented themselves by volunteering for duty in 1914 remind us that people’s everyday concerns didn’t simply stop because there was a war on.

Ordinary considerations filtered through to the theatres of war too. In a letter to his wife dated 1st October 1916 (touchingly appended ‘after tea’), William Anderson described a recent spate of desertions. The effort, he concluded, wasn’t worth it. Not only would it risk a military tribunal, but it would see the deserter’s ‘pay interfered with’. For modern eyes trained to see desertion rewarded with an automatic firing squad, this is a salutary reminder that more ordinary punishments loomed larger in the minds of the men involved. Capital punishment falls outside the 21st century British experience, but having one’s wages docked (and worse, having to explain the shortfall to one’s spouse) does not.

This everyday, in-the-moment correspondence challenges the received view of the war. It was perhaps the time of year, but as I strolled around the exhibition space, I recalled the words of Philip Larkin, who, in MCMXIV, commented satirically on the lines of 1914 volunteers, ‘grinning as if it were all an August Bank Holiday lark’. Larkin wrote from an historical perspective (the war had concluded before he was born) and made his comments around the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of the war. His work was a product of, and contributor to, the popular idea that the war was received as an excellent thing, a jolly good clearing-out that would settle things once and for all and, famously, all be over by Christmas. In this view, the people of 1914 were naive at best, outright fools at worst, blissfully unaware of the devastation that was about to be wrought upon them. ‘Never such innocence’, continued Larkin ‘never before or since…never such innocence again’.

Again, this view is challenged by the off-hand testimony of the people who were actually there. From Street to Trench contains a series of letters written by Merseysider Ada McGuire to her sisters. The first, dated 7th August 1914, expressed the ordinary concern for a loved one; ‘thank God Ralph won’t have to go to the war’, she writes, ‘this terrible war’. That date again: 7th August 1914. The British Expeditonary Force only arrived in France that day and HMS Amphion had been sunk a day earlier, causing the first British casualties of the war (facts that may not have even been known to Ada McGuire as she set pen to paper). The precise, unprecedented terribleness of the war was not yet known either, and still it warranted a horrified adjective. August or otherwise, faces such as Ada McGuire’s were hardly grinning, even at that early stage.

Larkin’s commentary pointedly drew a comparison with the lines of volunteers and those who queued up at the gates of football stadiums on Saturday afternoons. The two were not mutually exclusive and football, as well as sport in general, was just as affected by the war as any other aspect of life. Appropriately, for an exhibition focused on the North West, football has a prominent place in From Street to Trench (the Professional Footballers’ Association is a key supporter). The involvement of the game is demonstrated through examples of that perennial collector’s item, the matchday programme. The edition from Liverpool vs Rochdale on the 16th October 1915 (they drew, two goals apiece) features a recruitment advert for the County Palatine Royal Army Medical Corps), demonstrating how the authorities sought the attention of young men where they knew they could find them -in the stands. A later programme, from Manchester City vs Liverpool on the 16th November 1918 (Liverpool took victory after putting two past a goalless City), shows the state of the game in the immediate wake of the Armistice. A letter from City player Peter Gartland reveals his sorrow at having to ‘finish with the game my heart and soul were in’. His career had been brought to an end not long before when he lost a leg after receiving a ‘wound just the size of a threepenny piece’. He remained stoical and wished the club every success and that he hoped to ‘see them at the top this season’. His desire to look ahead was shared by the club’s officials who used the programme to describe their plans for the future of the game. They were glad to seen an end to ‘the Awful Tragedy’ and wanted to carry on for ‘the good of the boys’. International fixtures would be a non-starter, but there was every possibility of inter-league matches. Football, and life itself, must go on.

From Street to Trench is at Imperial War Museum North. Admission free.

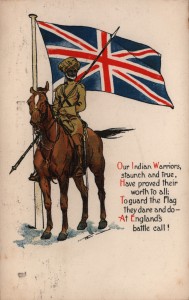

sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the

sending its young men off to fight on land, sea and air, by contributing materially to the war effort or by banding together as the costs of the conflict grew, every corner of the country was affected in some way by the First World War. The local impact of the war remains a powerful one and is central to the