Michael Noble reports from the Hidden Histories Autumn Roadshow Programme

We’ve just completed our first round of roadshows, which took us to Nottingham, Leicester and Derby to share some of our work and ideas. We were very pleased to welcome members of community groups, interested individuals and staff from the Heritage Lottery Fund and the local councils who came along to listen and participate.

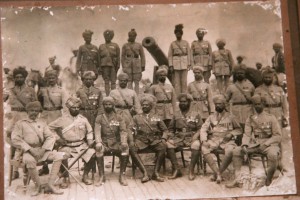

Our Principal Investigator, John Beckett outlined his idea of ‘Hidden Histories’ and explained that we were interested in examining the stories of people who took part in the First World War but who do not fit the conventional model of a Tommy. To illustrate his point he presented a picture of Wilfred Owen next to a similarly-posed portrait of a Daffadar (Sergeant) of the of the 14th Murray’s Jat Lancers of the Indian Army and asked the audience to name them. Many of the attendees could identify Owen, none could name the Daffadar. And neither could we. His, John pointed out, is a hidden history.

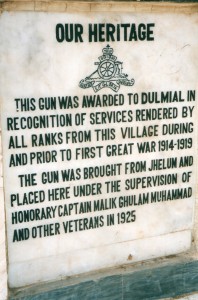

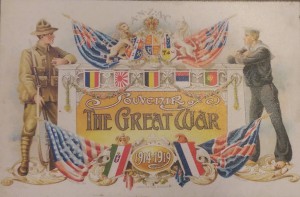

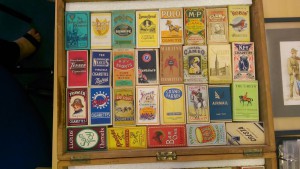

We had the privilege of hearing from community representatives who wanted to share their ideas for commemorative projects. In Nottingham, Dr Irfan Malik presented the story of the Dulmial Gun (which we blogged about here) and described its importance to his family. Local artist Joy Pitts gave us an insight into her work and her ongoing Military Boots project and Eric Pemberton of the African and Caribbean organisation Banyan presented his painstakingly researched calendar, which he also brought along to the Leicester event. He was joined at Leicester by the Ramgarhia Social Sisters who have recently returned from a visit to the Empire, Faith and War exhibition and who have been inspired to create a tapestry work to tell the stories of the Sikh soldiers in the First World War. Also at Leicester was Roy Hathaway, who has amassed a collection of around a quarter of a million vintage cigarette cards, many of which feature soldiers and imagery from the war. Roy was kind enough to display some of his collection at the event. In Derby, we were joined by Daljit Singh Ahluwalia MBE and his wife Parkash, who are planning to develop a local exhibition of the Sikh contribution.

All three events featured a short talk given by one of our Co-Investigators. In Nottingham and Derby, Natalie Braber presented her work and answered the question of what a linguist has got to do with the First World War. In Leicester, Mike Heffernan gave a talk on the Imperial (now Commonwealth) War Graves Commission and the effort to memorialise the dead in an appropriate and fair manner.

We were encouraged by the enthusiasm shown by the attendees and will be pleased to work alongside them as they develop their projects. If you were unable to come to any of the roadshows, but would like to get involved, please contact us for a friendly discussion.