It has been estimated that by late 1914 fifty-five different nationalities were represented at the Western Front, creating a melting pot of identity, experience and language. The Centre for Hidden Histories’ resident linguist Dr Natalie Braber examines some of the inventive terms that the soldiers used to describe their comrades and enemies.

As a result of World War One, people came into contact with one another more than they otherwise would have and one of the effects of such contact is a change in language. This can be due to ‘invention’ of new words, or ‘borrowings’ from other languages. A very fruitful field for linguistic study is to examine how soldiers from countries are referred to. British soldiers were often referred to as ‘Tommy’ from Tommy Atkins, the name for the typical English soldier. This term dates back to 1815 and became immortalised in the Rudyard Kipling poem ‘Barrack Room Ballads’ published in 1892. This term was used throughout WW1 by both sides.

There were also names given to soldiers of other nationalities: Italians were referred to as ‘Macaroni’, Portuguese as ‘Pork and Cheese’, ‘Pork and Beans’ or ‘Tony’, Austrians as ‘Fritz’ and Turkish soldiers as ‘Jacko, Johnny Turk or Abdul’.

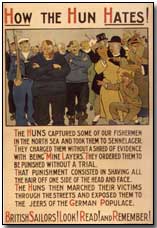

There are many different terms used for German soldiers. Reports of the ruthlessness of the German army in China in 1900 refer to the use of ‘Hun’ by the German emperor as a symbolic ideal of military force and so this name came to be applied in 1914, in particular when discussing atrocities. The terms ‘Hun’ and ‘Boche’ were also in use throughout the war. Boche is said to have derived from a slang French word ‘caboche’ meaning ‘rascal’. Other suggest the term ‘cabochon’ relates to ‘head’ and especially a big thick, head. It seems to have been used in the Paris underworld from about 1860, with the meaning of a disagreeable, troublesome fellow. By 1916 the term ‘Jerry’ was in general use. The first time it was used in the Daily Express it was explained ‘The ‘official’ Irish designation of the enemy’. This term seems to carry more connotations of weariness and familiarity than hate.

As well as names for other soldiers, the men on the front were inventing new words due to contact with other soldiers from other nationalities as well as other parts of the United Kingdom. ‘Clink’, originally a London word for prison became widely adopted by men from around the country. A writer to The Times in January 1915 proposed that ‘the majority of colloquialisms used by soldiers have a Cockney origin’. Given the number of British personnel stationed on French territory it is unsurprising that many French terms were picked up and adapted. The increased use of ‘souvenir’ in place of ‘keepsake’, and ‘morale’ in place of ‘moral’ can be dated to this period. Perhaps the term most widely-used by British soldiers was ‘narpoo’, used to mean ‘finished’, ‘lost’ or ‘broken’, deriving from the French il n’y a plus meaning ‘all gone’. Terms were adopted and adapted from almost all languages that were in use in the combat zones. From Hindi came ‘blighty’ (meaning ‘foreign’ so applied to British soldiers, and thus signifying ‘Britain’) and ‘khaki’ from an Urdu word for ‘dust’. From Russian came ‘spassiba’ (thanks), from Arabic came ‘buckshee’ (free), and from German achtung came ‘ack-dum’ (look out).

Since my father actually fought in both world wars and as a German had strong (family) ties with France and the Alsace I was always interested in the origins of the term “boche”. There seems to be an equally intractable derogatory Dutch term for the Germans “moffen” of which the origin is equally uncertain. The “hun” is still alive and well and dates back to Wilhelm II, the last German Kaiser’s speech to the soldiers sent to China where he explicitly used the terms to tell how he expected them to behave. So this term at least has a “justification”. The Austrian “Fritz” though I am not sure about. In my book it also refers to the Germans more than the Austrians (Germans often being christened “Friedrich” or Frederick after “Frederick the Great” and could be related the Germans referring to Frederick the Great endearingly as “old fritz” (“Alter Fritz”).